Equity in evidence: how the pharmaceutical industry can advance health equity to drive better outcomes and value in health care

The growing focus on health equity presents a vital opportunity for the pharmaceutical industry, allowing stakeholders to take concrete steps to integrate equity into market access strategies. By fostering collaboration between payers, health technology assessment (HTA) bodies, and pharmaceutical manufacturers, with a shared commitment to health equity, the industry can drive significant change and pave the way for a more just healthcare system.

At the World Evidence, Pricing and Access Congress 2024 (March 12–13; Amsterdam, The Netherlands), Dr Jonathan Pearson-Stuttard (Head, LCP Health Analytics & Chair, Royal Society for Public Health) tackled this head-on in his presentation entitled, “Prescribing equity: the pharmaceutical industry’s vital role in addressing health inequalities”. In this Deep Dive, we summarize some the key points discussed in the session, such as the growing importance of health equity for stakeholders including governments, payers, HTA bodies and the pharmaceutical industry. The session also explored the vital role of real-world data (RWD) in understanding the complexities involved and provided practical solutions for integrating equity considerations into market access strategies.

A growing challenge: why health equity matters to payers and HTA bodies more than ever before

Dr Jonathan Pearson-Stuttard began by discussing the underlying importance of health equity. He highlighted a worrying trend of widening health inequalities, presenting two case studies that, while demonstrating varying degrees of disparity, highlight a consistent pattern: factors including socioeconomic deprivation, ethnicity and geographic location all contribute to health inequalities. First, looking at life expectancy in England, data suggest a significant disparity in life expectancy across different regions, with a gap in life expectancy at birth of 21 years in women and 27 years for men across small geographies. Additionally, since 2014, a concerning number of people in England have seen a decline in life expectancy, with estimates suggesting one in five women and one in nine men experiencing a decrease. In comparison, in more affluent regions of the country, life expectancy has increased. Second, looking at breast cancer mortality in US women, a significant variation is observed according to ethnicity, with 40% higher death rates in Black women with breast cancer compared with White women with the disease. This disparity worsens when examining specific subgroups – young Black women under 40 have a twofold higher risk of dying from breast cancer compared with young White women in the same age group.

Pearson-Stuttard moved on to discuss the changing perspectives on the value of health and the value of health equity, with HTA bodies needing to adopt a more holistic approach when evaluating medicines. Three factors have influenced this change:

- Economic inactivity: A major problem for high-income countries over recent decades caused by the increase in multimorbidity, particularly in the working population, which lead to inequalities in economic outcomes.

- COVID-19 pandemic: The pandemic exposed existing inequalities in health, through the risk of contracting COVID-19 and associated health outcomes, as well as underlying health-related factors including impact on jobs, and wider societal and economic issues.

- Valuing medicine holistically: Whilst there is much work still to be done to address equity considerations, some progress is being made; for example, in the UK, the 2024 voluntary scheme for branded medicines pricing, access and growth (VPAG) between the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England and the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) includes tracking of variation in the uptake of NICE recommended medicines between Integrated Care Boards.

One size does not fit all: tackling nuanced complexities in health equity considerations

Pearson-Stuttard reiterated the importance of a holistic view of health equity for market access, acknowledging that, “one size does not fit all”, since domains of equity vary at a patient, disease, market and HTA level. Taking the example of sickle cell disease, this is significantly more common and has worse outcomes for people of Black ethnicity compared with those of other ethnicities, which is consistent across and within countries. The impact goes beyond poor health outcomes, particularly as the disease affects younger individuals, hindering economic activity and incurring broader societal consequences. This highlights the presence of inequalities within a specific ethnicity.

Looking within specific conditions, health equity can vary across regions and markets. Using the example of cardiovascular disease, Pearson-Stuttard highlighted the differences in equity considerations between the UK, USA and Chile.

In the UK, deprivation is measured, with research showing that individuals from the most deprived regions experience their first stroke 7 years before individuals from the least deprived areas. The US prioritises income as a measure, In the US, research has shown that household income and blood pressure have an inverse relationship, with lower income groups having an increased risk of high blood pressure and cardiovascular disease risk. Whereas in Chile, it has been shown that even with rising incomes, the risk of dyslipidemia remains higher for individuals with lower education.

“Not only does the domain of equity matter according to the disease, it also matters according to the market and to the population. When generating evidence that’s relevant for payers and HTA bodies, this will vary according to the disease, according to the population and according to the market.”

Pearson-Stuttard moved on to discuss the growing body of evidence examining the increasing discussion around health equity. A recent study by Breslau et al. investigated the incorporation of equity considerations within economic evaluations conducted by HTA bodies. Of 53 guidelines evaluated, two-thirds mentioned equity, with 43% of the guidelines recommending the inclusion of health equity considerations in qualitative discussions. This research highlights that health equity is “on the agenda of HTA bodies” but that implementation and quantification remains a challenge.

Pearson-Stuttard noted that whilst recent advancements in medicines have significantly improved population health and reduced healthcare disparities, the evidence generated does not typically consider the impact on health equity. By the pharmaceutical industry generating evidence that demonstrates this, the full value of these medicines can be captured to ensure equity becomes a core consideration in market access. Pearson-Stuttard provided four specific use cases in where focused equity evidence could mean new medicines have greater and more sustained impact.

Feasible solutions: meaningful steps to embed health equity across market access

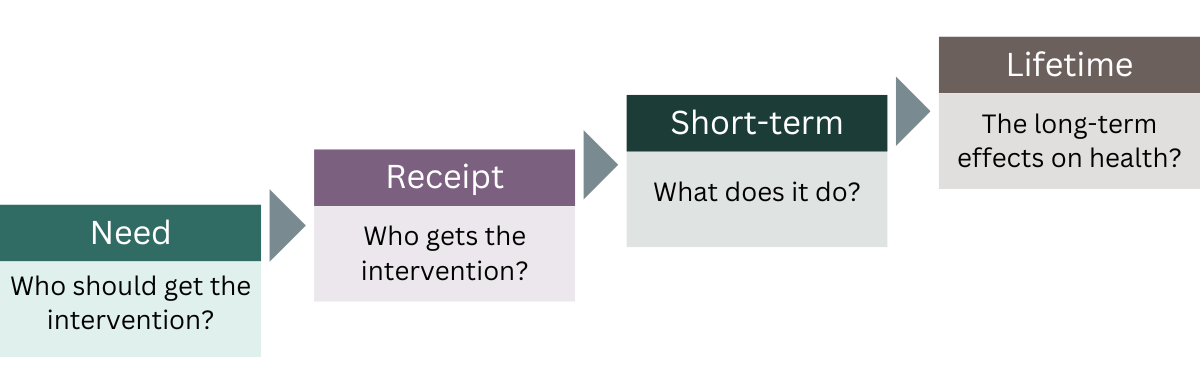

Pearson-Stuttard went on to outline three key evidence types to work toward ‘normalizing’ health equity consideration with HTA bodies and payers. He presented the concept of the “staircase of inequality” – a framework developed to identify the impact of health programs on health inequalities across different populations.

Inequalities can affect each step, with social determinants of health, often outside the control of healthcare systems, influencing the ‘need’ and who should get the intervention. Inequalities in access, which are determined by healthcare systems, affect who gets the intervention (‘receipt’), whilst the remaining steps of ‘short-term’ and ‘lifetime’ outcomes need to consider more holistic health and societal impacts.

-

Evidence of unmet need

Previously, data collection and analysis has been a key challenge in informing equity considerations; however, the availability of broader real-world datasets and real-world evidence (RWE), along with innovative methods like transportability analysis, provides the tools needed for in-depth analysis to identify variations in unmet needs, which groups face the highest risks, and how access and uptake differ across populations. Pearson-Stuttard stressed the importance of comparative effectiveness in assessing the “true value” of new medicines. This point was further emphasized in research by Dr Ben Bray and LCP Health Analytics in collaboration with Novo Nordisk that investigated inequalities in healthcare resource utilization costs for people with Alzheimer’s disease in England. The study shows significant cost variations in health care for people with the same condition, with 20% of patients with the highest costs incurring 20-times more expense than the lowest 20%. Understanding variation in unmet need is crucial for both healthcare payers and HTA bodies to start taking tractable action.

-

Evidence for equitable access and uptake

Pearson-Stuttard discussed the ‘second stair’ on the ‘staircase of inequality’ by describing a study looking at the effects of ethnicity, sex and age on a range of lung cancer treatment options. The research showed age as the largest driver inequality.

“It’s important to look across all the domains specific to the disease and specific to the population to determine what is most important and how can we tackle those… What’s the value of closing that gap? What would it mean to ensure that the access to these medicines or innovations is the same for everyone? What does that mean for health outcomes? What does that mean for payer-relevant outcomes? And what does that mean for broader economic and societal outcomes?”

-

Comparative equity effectiveness evidence for HTA

Within the HTA process itself, Pearson-Stuttard discussed several methodological approaches towards embedding comparative equity evidence, with stakeholder familiarity with these evidence methods a key obstacle currently to broader utilization. Distributional cost-effectiveness analysis (DCEA) can help understand the tradeoffs between maximizing health and promoting equity by considering how the costs and benefits of an intervention are distributed across different populations, such as those defined by socioeconomic status, ethnicity, age or geographic location. This allows for quantification across different domains of equity to be incorporated in HTA decision-making.

Extended cost-effectiveness analysis (ECEA) is another approach used to consider how the costs and benefits of an intervention impact different populations. ECEA is used more appropriately in countries without a national single payer and where there is a financial risk to individuals (catastrophic health expenditure). Pearson-Stuttard discussed the example of malaria interventions in Ethiopia, where the ECEA showed the poorest population would see the greatest financial risk protection benefits.

Partnerships: collaborative approaches towards putting health equity into practice

Pearson-Stuttard ended the presentation with a discussion on the practical steps needed to achieve health equity, proposing an “Equity Framework” that could make “meaningful strides towards embedding health equity in market access. The standardized framework would provide guidance to manufacturers to foster collaborative and consistent progress. This would also build on the success of the NICE RWE framework, which has been collaborative and iterative, and provided very clear progress towards incorporating RWE in HTA decisions. Systematic and standardized guidance will be important across some of the key elements including:

Pearson-Stuttard ended the presentation with a discussion on the practical steps needed to achieve health equity, proposing an “Equity Framework” that could make “meaningful strides towards embedding health equity in market access. The standardized framework would provide guidance to manufacturers to foster collaborative and consistent progress. This would also build on the success of the NICE RWE framework, which has been collaborative and iterative, and provided very clear progress towards incorporating RWE in HTA decisions. Systematic and standardized guidance will be important across some of the key elements including:

- Appropriateness of the data sources to capture health equity considerations

- Population considerations including domain of equity according to disease, market and population

- Demonstration of the methods, making it easier for all stakeholders, including HTA bodies, payers and pharmaceutical manufacturers, to become more familiar these new approaches

- Partnerships to ensure meaningful progress and knowledge sharing

Audience Q&A

Where are equity considerations in market access being used in practice?

Pearson-Stuttard addressed this question by referring back to the publication by Breslau et al., which showed that across different HTA bodies, equity considerations have predominantly been included in qualitative discussions. This was also noted in the 2023 white paper published by the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER). He observed that no HTA body has yet included quantitative assessment of health inequalities and, in particular, a standardized approach.

On the payer side, Pearson-Stuttard referred to the UK VPAG agreement, which as part of the agreement will be tracking the inequalities in access to new medicines across the UK at the local level (via NHS England), as well as through clinical specialty leads. This is the first real example in which the tracking of inequalities has been incorporated into an agreement between the pharmaceutical industry and a payer.

What can the pharmaceutical industry do to address inequities?

Pearson-Stuttard acknowledged that achieving health equity is a long-term goal, requiring ongoing collaboration among HTA bodies, payers, the pharmaceutical industry, patient groups and clinicians. While recognizing the complexities involved, he emphasized that robust evidence is the key to making progress.

“It’s about generating the evidence across that ‘staircase of inequality’ and the variation of unmet need through to more substantive collaborative projects with payers and HTA bodies towards familiarizing them with new methods, their limitations and the data required to put them into action. Generating the evidence then itself creates a value question around why equity should be incorporated.”

About the speaker

Dr Jonathan Pearson-Stuttard is Head of Health Analytics at Lane Clark & Peacock (LCP). Jonny completed his medical training at the University of Oxford followed by MSc Epidemiology and PhD Diabetes Epidemiology at Imperial College London. As a Public Health Physician and Epidemiologist, he is Chair of the Health Inequalities Programme Board at Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and Chair of the Royal Society for Public Health. He leads a multi-disciplinary analytics team at LCP who work across the life-sciences sector to provide actionable insights and shift healthcare systems from importers of illness to exporters of health.

Sponsorship for this Deep Dive was provided by LCP Health Analytics.